A Community-Centered Approach to Malaria Elimination in Honduras

Hundreds of community volunteers in remote areas are helping to inch the country closer to eliminating malaria by 2028.

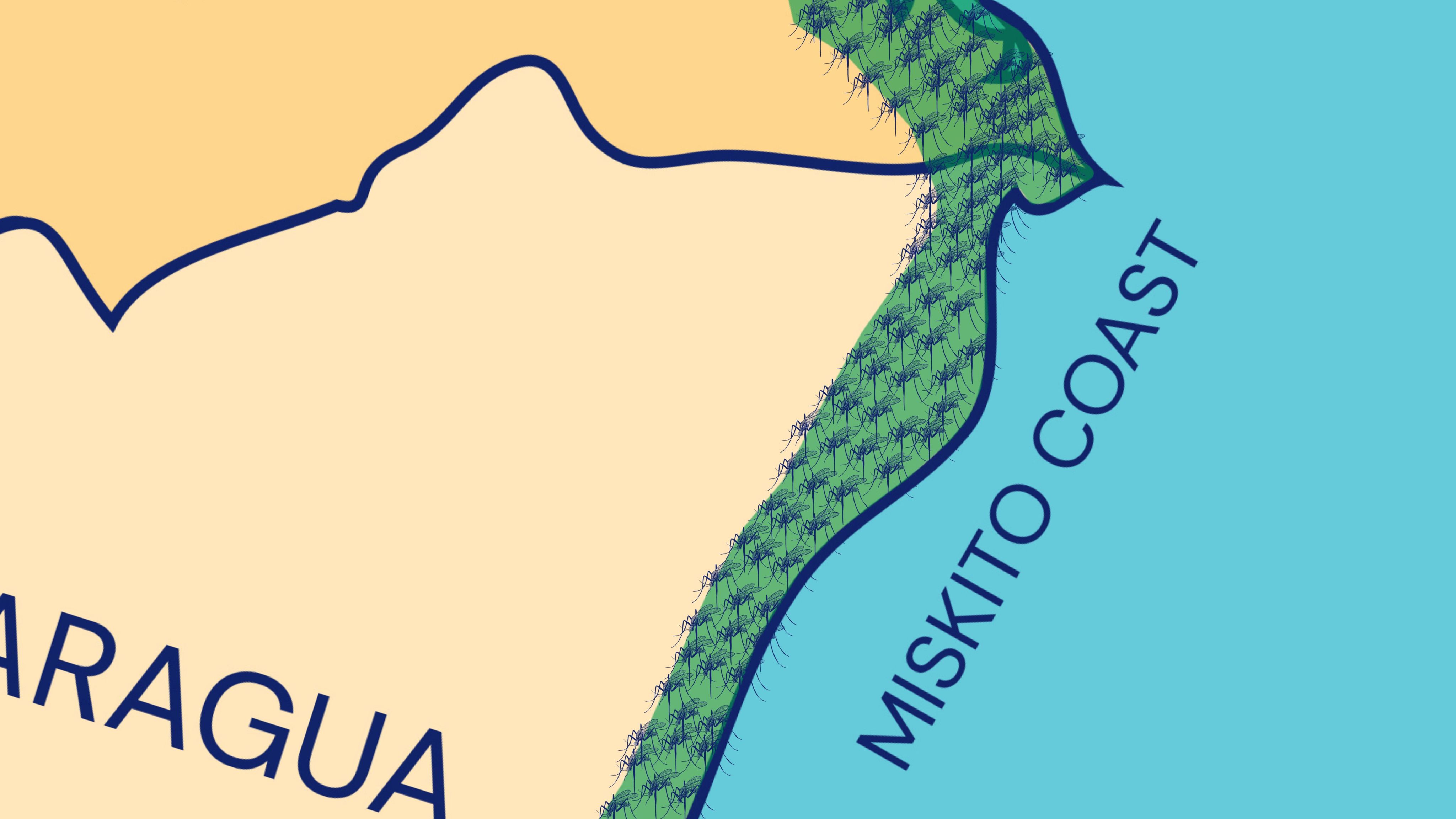

In Gracias a Dios, one of Honduras' 20 regional health departments, a majority of the indigenous population is located along the Miskito Coast. This community is exposed to high rates of bites from Anopheles mosquitoes—the vector responsible for malaria transmission.

People who contract malaria typically experience high fevers, shaking chills and flu-like symptoms such as headaches and fatigue. If left untreated, this strain can cause brain damage to those who are infected.

Malaria can be deadly if untreated, leading to more than 600,000 deaths annually, most of which are in Africa, according to the latest figures. In the last 10 years, Honduras has only reported one death from malaria. However, even in non-fatal cases, malaria can have long-term health effects, particularly in children, including cognitive, motor skill and visual coordination impairment.

In 2022, Honduras reported over 3,500 new malaria cases. Of these, 95% were in the Miskito area of Gracias a Dios, known as La Mosquitia. Together with the Miskito area of Nicaragua, this area has the highest malaria cases in all of Central America.

But a malaria-elimination initiative by the Ministry of Health in partnership with Global Communities is helping change these statistics.

60,000

deaths annually worldwide;

and more than

3,500

new malaria cases;

95%

malaria cases found in the Miskito area of Gracias a Dios;

1

death reported in the past decade in Honduras.

After graduating from medical school in 1988, Francisco Medina Ramos chose to work in La Mosquitia, where he treated countless malaria cases. Ramos became a passionate advocate for malaria elimination as he saw the impact of the disease — and as it hit close to home.

"Two of my children had malaria, I treated them…Thank God they lived."

According to Ramos, now the National Malaria Coordinator at the Ministry of Health, high incidences of malaria are common amongst those who live in poverty. Studies show these individuals are less likely to seek prompt treatment, which can help reduce long-term effects.

According to the World Bank, nearly 72% of the Miskito people face multidimensional poverty — meaning they live below the national poverty line and also lack access to education and safe housing, the latter of which is closely connected to increased cases of malaria. Malaria infections also create a ripple effect, further marginalizing individuals, Ramos explained.

Those most likely to get sick most are the economically active population. These people get sick, they stop working, they stop producing. It affects the life of the person, but it also affects society.

The challenge remains. I believe that we … really have to take it [malaria elimination] to zero until the end, whatever the cost. We all have to climb the steps at the same time and say we arrived, in the end, [to where] we wanted.

In 2000, Honduras had more than 35,000 malaria cases, but by 2019, the country reported only 386 malaria cases.

This incredible feat resulted from collaborative efforts, including by the Ministry of Health, with support from Global Communities, which has provided financial and technical assistance to malaria elimination efforts in Honduras since 2009.

However, the downward trend of malaria cases led to an uptake in 2020 as coronavirus lockdowns confined people to their homes and health facilities paused services, including malaria elimination activities.

As a result, Gracias a Dios saw an increase in malaria cases in 2020. While this threatened progress made in the last two decades, malaria cases in the region have declined year after year as malaria elimination activities resumed.

This means eliminating malaria is within reach, said Miguel Bobadilla Cardona, a Monitoring and Evaluation Officer with Global Communities.

It is a disease that can be prevented, if we all participate and if we adopt behavioral practices that are friendly to healthy coexistence.

These behaviors include community members adopting protective measures such as using bed nets, monitoring and reporting disease symptoms and spraying insecticides where mosquitoes reside indoors. However, one of the challenges is the remote nature of the communities on the Miskito Coast. Accessing these remote communities may take a full day of travel from major Honduran cities, first by plane and then by boat.

Given some communities' inaccessibility and lack of local health facilities, the Ministry of Health identified, trained and mobilized a vast network of locals, known as volunteer collaborators or ColVol. These volunteers help prevent transmission and monitor malaria through home visits, mosquito net installation, and indoor spraying in houses (intra-domiciliary residual sprays). ColVols, organized in malaria hotspots, also provide supervised treatments to malaria patients.

Doña Sussy, a grandmother and Miskito community member has spent the last 20 years as a health volunteer in her community and currently serves as a ColVol.

Like her colleagues, she is outfitted with a vest, cap, t-shirt and Ministry of Health ID card to identify her as a trained volunteer. In addition to attending to malaria cases in her home, she travels through her community in the Gracias a Dios region with a backpack full of malaria detection tests to conduct home visits and screen community members experiencing malaria-like symptoms.

I love my people. They come to my house, and I look after them at night, in the morning, at whatever time.

People respect me. They look for me to test them for malaria, even if they are from other neighborhoods.

Partnering with ColVols like Sussy has been invaluable in the early detection and treatment of malaria, said Cardona, as it enables community members to "become the architects of their healthy environment."

Collaboration is critical.

These joint efforts by the Ministry of Health and Global Communities have led to Honduras being on track to reach the World Health Organization's malaria-free status by 2028.

Since January 2021, The National Honduras Malaria Elimination Strategy has

trained

338

ColVols trained,

and installed more than

100,000

mosquito nets.

From 2024-2026,

122

ColVols will be deployed,

more than

110,000

mosquito nets will be installed,

and more than

7,500

homes will be sprayed outside the Miskito area.

Honduras’ National Malaria Elimination Strategy

Global Communities' current program, the National Malaria Elimination Strategy, launched in January 2021 and will operate through December 2023. It is being implemented in 12 regions, including Gracias a Dios, with 1.3 million inhabitants. The $4.03 million program is funded by Roll Back Malaria (RBM) through the Global Fund to Fight Malaria.

The program's goals include:

- Supporting the national goal of 150,000 suspected malaria cases undergoing parasitological testing;

- Installing more than 101,800 mosquito nets;

- Conducting more than 52,000 indoor sprayings; and

- Training more than 330 volunteer collaborators.

Global Communities implements the following four main strategies to eliminate malaria in Honduras:

Strategy 1: Case Management

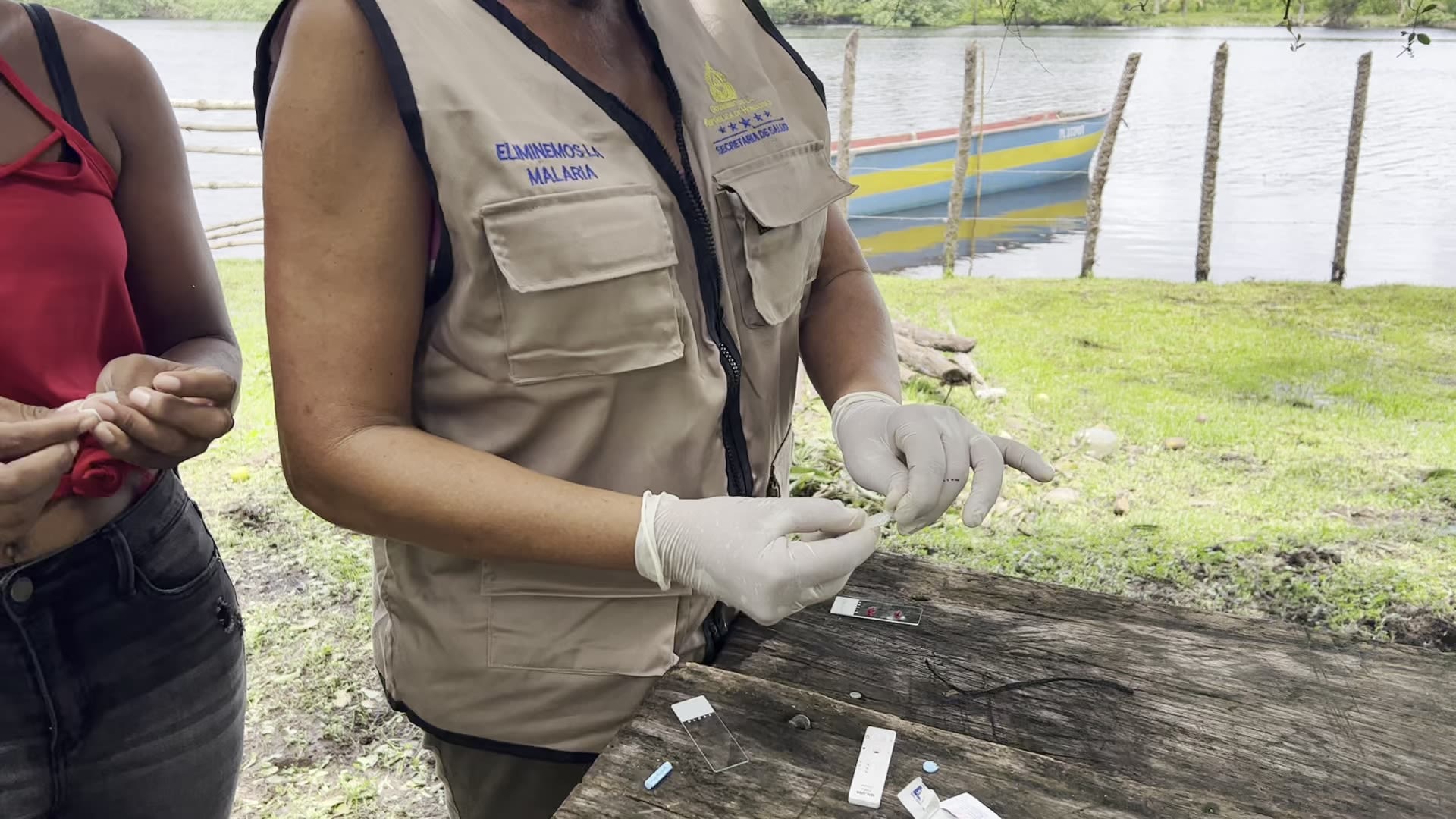

Case management is conducted through the early detection and treatment of malaria cases. Volunteer collaborators and health centers take blood samples from individuals who report malaria symptoms to conduct Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs).

Test results are typically available 20 minutes after the blood specimen is collected from the patient. If malaria is detected in the sample, infected individuals are treated with chloroquine and primaquine, anti-malaria medications used to prevent and treat the disease.

Strategy 2: Vector Control

To prevent infections, the Ministry of Health, through Global Communities’ support, deploys health workers and volunteers to install mosquito nets and provide intra-domiciliary residual spraying in the homes of populations in high transmission areas.

This helps interrupt active malaria transmission by preventing mosquito bites. To maintain sustainability, lost or damaged mosquito nets are replaced after two continuous years following a universal campaign.

Strategy 3: Program Management

Global Communities supports the Ministry of Health in planning, monitoring and evaluating the programmatic and financial performance of the National Malaria Elimination Strategy throughout the project. This ensures the strategy is cohesive, sustainable and well-positioned to make the largest possible impact.

Strategy 4: Sustainable Resilient Health Services

To ensure long-term and sustainable malaria prevention in Honduras, Global Communities supports developing epidemiological information systems and malaria prevention services, including coordinating medicine and health supplies to reach communities most impacted by malaria.

At a time when disasters and disruptions are becoming more common and catastrophic, Global Communities, together with our local partners, equips communities with the training, tools and resources they need to recover from crises and build long-term resilience in the face of constant change.

From prevention and adaptation to positive transformation, we focus on solutions that center local voices and expand opportunities for growth, leadership and advancement.