How Brazilian Farmers are Modernizing Agricultural Practices to Become Climate Resilient

Amid crises such as climate change, which threaten the livelihoods, food security and well-being of smallholder farmers in Brazil, Global Communities and its local partners are equipping thousands of farmers with training, tools and resources to build long-term resilience.

Antônio Albédio Soares has been farming for as long as he can recall. The 45-year-old second-generation farmer is from the small town of Novo Oriente in Ceará, located in Brazil’s Northeast region.

But farming — even for subsistence purposes — has become increasingly difficult. Rain patterns in Brazil have changed significantly in recent decades and temperatures have risen by 0.5°C. The Northeast region where Soares hails is semi-arid, limiting farming to only two or three months of the year.

In combination with other challenges farmers face such as poor yields, low profitability due to middlemen, and the painstaking work of manual farming due to a lack of access to machinery and technology, farming has become less feasible and appealing.

Antônio Albédio Soares

Antônio Albédio Soares

“The climate conditions do not allow us to produce as they used to. It is very expensive,” Soares said.

Wanting a different life from those in his community who struggled with farming, Soares moved to São Paulo, the most populous city in Brazil, when he turned 18, and eventually moved to the capital city of Rio de Janeiro.

He got a job in construction, worked his way up from an administrative to a managerial role and then went his own way, deciding to start his own construction company.

“I went in search of a better life … [but] I always dreamed of returning to my hometown,” he said.

Economic opportunities were few and far between in Novo Oriente, however, and Soares ruled out working in agriculture.

“The land itself has expenditures to maintain such as livestock, taxes, and hiring occasional help, and yet, what we can harvest is barely enough for subsistence,” he explained. “We always had to use the money we made in the city to maintain the land.”

Soares’ experiences are consistent with data showing that climate change and food insecurity are worsening in the country. In 2014, the United Nations recognized Brazil for its “outstanding progress in fighting hunger,” but today, nearly one in every three people in the country experience moderate or severe food insecurity, according to the World Bank. This means these individuals have been exposed to low-quality diets and might have been forced to reduce their food consumption because of a lack of money or other resources.

Amid these challenges, Soares heard that some farmers in his hometown were thriving. They told him about Prospera, a program which began in 2016 and supported them to boost their yields and transform their livelihoods by shifting from subsistence farming to producing larger outputs. That was all it took for Soares to pack his bags and leave life in the big city behind.

Twenty-five years after leaving his hometown, he moved back to Novo Oriente in 2021 to join others who were revitalizing the agricultural sector.

Creating an Ecosystem

for Farmers to Prosper

In Soares’ hometown, as is common in the Northeast region, corn is a staple in diets as it is consumed for breakfast and used in dishes such as the sweet corn cake pamonha and a soupy meal called canjiquinha, which involves corn grits.

But despite its central role in Northeastern culture, the region imports 90% of its corn, according to the Poultry Farming Association of Ceará. Traditional corn farming methods have been ineffective given the region’s dry climate and soil, and finding solutions is an arduous task.

Farmers begin by contacting seed companies to find out which seeds are best suited for their area. Then, they need to locate and rent the correct machines to help them plant the seeds. Without access to information on relevant agricultural methods, some farmers turn to YouTube for advice. A lot can — and often does — go wrong in the process, leaving farmers with low yields and discouraging them from corn production.

In an effort to promote sustainable agriculture, empower rural producers and strengthen the corn production chain, Global Communities partnered with the international agribusinesses Corteva Agrisciences, Yara International, Massey Ferguson and other local companies to implement Prospera.

Prospera, Portuguese for “prosper,” provides theoretical and practical training for farmers, rural extension workers and agricultural students and provides various technologies to support productive inputs, such as seeds, mechanization, fertilizers and pesticides. In essence, the program’s existence means farmers are no longer left on their own and doing the guesswork to grow corn, but are provided with the resources and knowledge to prosper in corn production — so they can feed their families and the region while profiting to secure their livelihoods.

Karla Skeff, program manager at Global Communities Brazil, explained how this unlocks new possibilities: “Climate change has been very devastating for farmers. Most producers have seen such extreme climate, either too dry or [too much] rain, that they became disheartened with harvesting. With technology, they see new horizons for corn. … They see the possibility of sustainable livelihoods.”

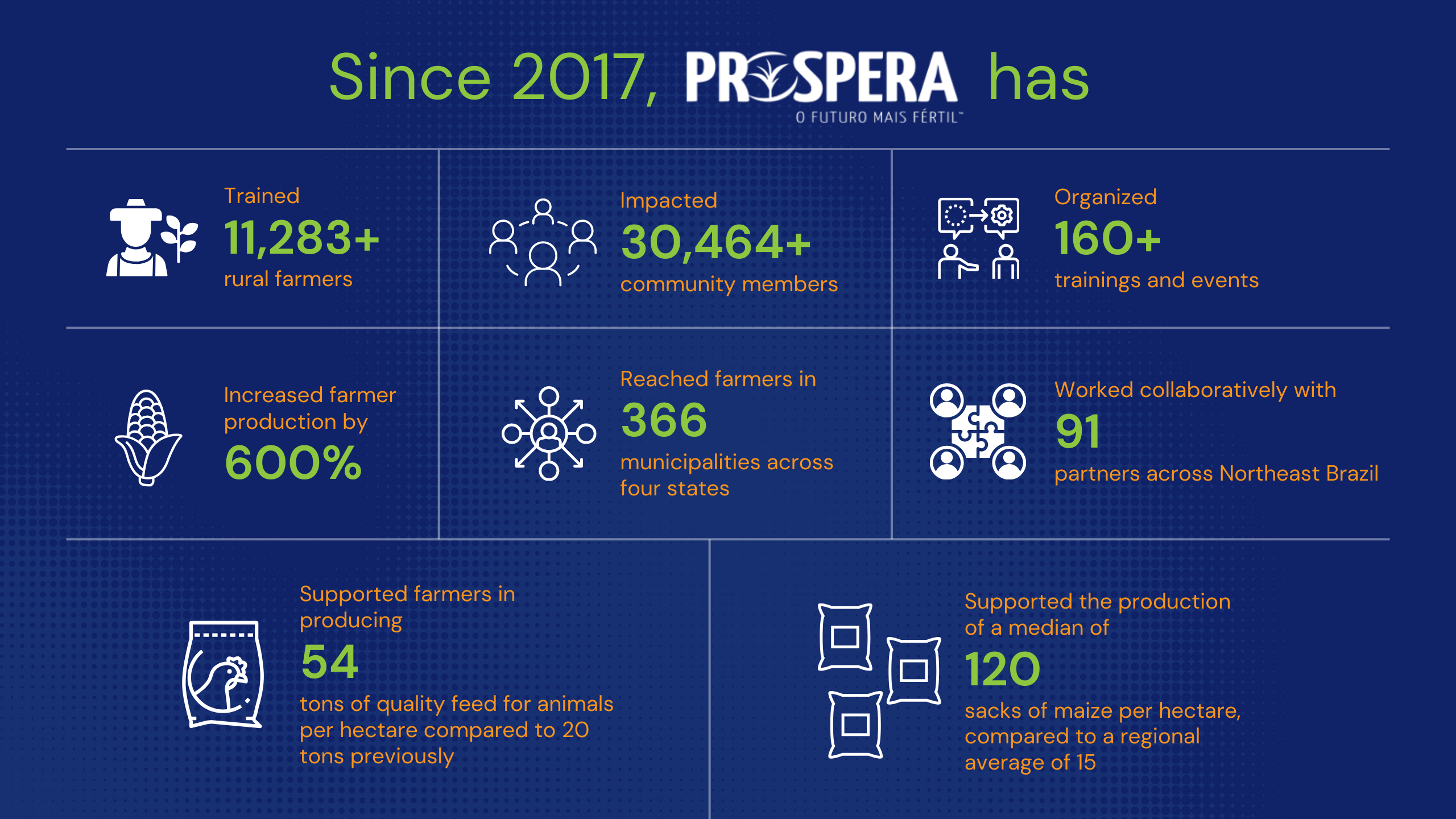

Prospera, which operates in four states in Northeast Brazil (Pernambuco, Ceará, Paraíba and Alagoas), has supported farmers in increasing their corn production from approximately 15 bags per hectare to 132. The program aims to reach and support 50,000 farmers by 2025.

Through Prospera, farmers are encouraged to form community groups to collectively negotiate and aggregate logistics and inputs in order to reduce costs. Prospera also encourages participating farmers to issue invoices, which helps formalize their work and makes them eligible to receive government pensions in retirement.

The Four Components of Prospera

Knowledge Capital

Prospera focuses on understanding agricultural challenges in the Brazilian Northeast to support farmers with the best technology and stewardship recommendations to obtain increased and sustainable yields. This knowledge supports farmers in managing risks.

Technological Capital

The program's focus on utilizing modern technology ensures farmers have better tools to increase productivity. When Prospera started in the region, we tracked an increase in agricultural productivity from an average of 10 bags/ha to 80 bags/ha of grains, with some areas reaching up to 191.73 bags/ha (Porteiras/CE).

Social Capital and Relationships

Prospera is made possible through 70 partnerships with state and municipal governments, universities, associations, unions, and public and private rural extension agencies, expanding farmers' social capital.

Human Capital

Prospera is working to impact more than 50,000 farmers in five years, enabling them to respond to local demands for corn by becoming self-sufficient in agricultural production.

Beyond Subsistence Farming

After joining the Prospera program in 2022, Soares received training at a demonstration plot and technical assistance on his own land. He had access to seeds, fertilizers and crop protection and was taught to leverage technology and machinery to harvest more productively.

Soares began harvesting corn on 10 acres of land and noticed dramatic changes in his harvest within months. While he previously generated 25 sacks of corn from an acre of land, since joining Prospera, he has produced an average of 84 sacks of corn — more than triple his previous output, allowing him to move back to Novo Oriente.

Naturally, his neighbors noticed and were curious about how they could see similar results. Soares, together with Prospera, hosted a one-day event on his land to share his learnings and answer their questions about leveraging technology in farming. More than 250 farmers from the community showed up, young and old alike.

“Since the 80s, youth have not seen any viable livelihood in the region. Now, I see young people start believing [in farming],” Soares said. “The older generation used to be very skeptical. Nowadays, after seeing the results with Prospera, I happily see my father talking to neighbors on the importance [of using technology to improve yields].”

According to Skeff, because Prospera combines knowledge and access to technology, it enables farmers to increase their yields and therefore, their income. Soares has used his increased income to invest in his farming even further. He planted corn on 10 acres in 2022 and expanded corn production to 47 acres the following year. In 2024, he plans to expand his corn production once again to a total of 73 acres.

“In Prospera, a farmer learns, earns and then reinvests [into expanding their farming]. It goes into a virtuous circle when the farmer becomes autonomous and becomes a multiplier of this knowledge since they are close to others in their community who also want to learn,” Skeff explained.

The program is also strengthening farmers’ climate resilience, supporting the local value chain and improving food security by helping the Northeast region become more self-sufficient in its corn production.

Shifting Paradigms and

Migration Patterns

According to Skeff, one of the most powerful outcomes of Prospera is the program’s ability to challenge dominant paradigms.

“We are challenging these paradigms that this region is not productive, that corn is not feasible for this region, that people will not learn or know how to use technology,” Skeff said.

As Prospera shows farmers that another way is possible, many are intent on staying and farming locally rather than migrating to cities to pursue economic prospects. This comes at a time when droughts and food security are expected to worsen in Brazil’s northeast.

Experts predict this will accelerate migration from the Northeast to the Southeast region and from rural areas to cities. In addition, this internal migration due to climate change may cause conflict related to land rights and access to resources, according to leading climate experts.

But some farmers like Soares are migrating in the opposite direction, and others are losing their interest in working in cities altogether. During Skeff’s field visits, she observes farmers as they learn about leveraging technology to increase their yields and sustain their livelihoods.

“They do the math in front of us and say if ‘I go to the city and get a minimum wage job, I can earn this [R$ 2.500/ USD $510], but if I farm, I can make this amount [R$ 4.500/ USD $918], so, why would I go to the city and work for others? No, I will work for myself,” Skeff said.

Ultimately, this leads to more farmers staying in Northeast Brazil, supporting their families through farming, and paving the way for future generations to do the same through sustainable climate-resilient farming practices, particularly as the impacts of climate change are set to worsen in the coming decades.

“It is important because they can stay on their land and their children can stay on their land … it’s sustainable,” Skeff said.

As a father of two, Soares hopes that one day, his children will choose to become third-generation farmers in a region where rural exodus is high.

“If you work in [the city] you can earn money, but when you work hand in hand with Prospera, you can develop the region,” he said.

At a time when disasters and disruptions are becoming more common and catastrophic, Global Communities, together with our local partners, equips communities with the training, tools and resources they need to recover from crises and build long-term resilience in the face of constant change.

From prevention and adaptation to positive transformation, we focus on solutions that center local voices and expand opportunities for growth, leadership and advancement.