Drought, Disaster and Hope

Fighting for Survival in Ethiopia

By: Maureen Simpson

Oyita Kala is no stranger to the unpredictability of a pastoral lifestyle, having spent decades moving herds across vast rangelands in southern Ethiopia in search of food and water.

Oyita Kala

Oyita Kala

Still, the last few years have taken a toll on him and other pastoralists in ways that have been increasingly difficult to manage due to multiple overlapping crises – from desert locust infestations and COVID-19 to natural disasters and ongoing conflicts.

“As a pastoralist, our assets are our livestock,” said the father of eight, “and I am the one who has no livestock. I lost all of my animals, a total of 40, over the last five years. … I don’t have the resources to feed my children.”

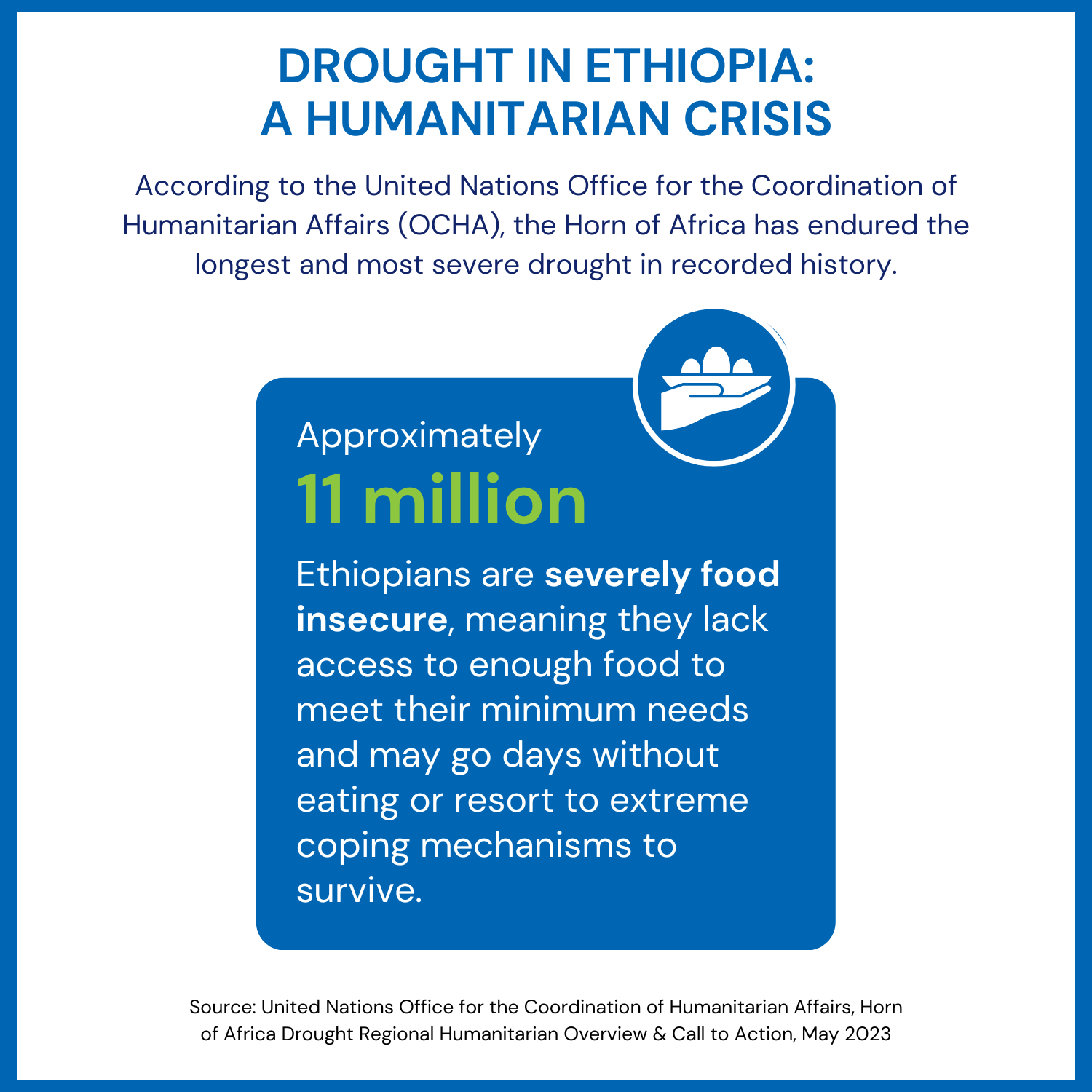

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the Horn of Africa has endured the longest and most severe drought in recorded history. Since late 2020, five consecutive failed rainy seasons have left at least 17.2 million people in urgent need of lifesaving and life-sustaining assistance in Ethiopia. Additionally, over 6.8 million livestock have died and many more are at risk, further jeopardizing the food security, economic stability and well-being of those who are dependent on rain-fed agriculture and pastoralism in the country.

Oyita Kala is no stranger to the unpredictability of a pastoral lifestyle, having spent decades moving herds across vast rangelands in southern Ethiopia in search of food and water.

Oyita Kala

Oyita Kala

Still, the last few years have taken a toll on him and other pastoralists in ways that have been increasingly difficult to manage due to multiple overlapping crises – from desert locust infestations and COVID-19 to natural disasters and ongoing conflicts.

“As a pastoralist, our assets are our livestock,” said the father of eight, “and I am the one who has no livestock. I lost all of my animals, a total of 40, over the last five years. … I don’t have the resources to feed my children.”

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the Horn of Africa has endured the longest and most severe drought in recorded history. Since late 2020, five consecutive failed rainy seasons have left at least 17.2 million people in urgent need of lifesaving and life-sustaining assistance in Ethiopia. Additionally, over 6.8 million livestock have died and many more are at risk, further jeopardizing the food security, economic stability and well-being of those who are dependent on rain-fed agriculture and pastoralism in the country.

“When I was young, 10 or 15 years ago, this area was very good,” said Boru Kala, a pastoralist from the Hamer woreda of South Omo.

"There was enough rain, and we had vast sorghum and maize. Also, the pasture for the livestock was very good."

“Now, the time is very difficult for us because there is not enough rain. … I lost 20 of my cattle over the past year.”

Safeguarding Progress and Delivering Swift Aid to Ethiopians in Crisis

In January 2020, with funding from the United States Agency for International Development, Global Communities embarked on a five-year initiative to help address many of the root causes of vulnerability for pastoral communities in Ethiopia and improve their ability to mitigate, adapt to and recover from conflict- and disaster-related shocks and stressors.

As part of the Resilience in Pastoral Areas South (RIPA South) project, Global Communities included a Crisis Modifier component that sets aside funds specifically for emergency response measures when certain thresholds and indicators are triggered.

At the outset of [RIPA South], we developed a strategy that when crises happen, we adapt the project itself and all the partners we work with to respond quickly using systems and structures developed during regular program implementation. It engages our local teams who are already working in these communities and know the context well in driving the emergency response and protecting any development gains that have been made.”

In March 2022, due to the unrelenting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid one of the driest rainy seasons on record, RIPA South activated its first Crisis Modifier to address the short-term urgent needs of the most vulnerable people living in the project’s five targeted zones: Borena, Guji, Liben, Dawa and South Omo.

Interventions were categorized into three windows: livestock support, multi-purpose cash assistance and access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Livestock Support

Aim: Save the lives of core breed livestock and improve livestock health, productivity and body condition

Interventions: Provide multi-nutrient livestock feed and fodder as well as voucher-based veterinary services

Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance

Aim: Improve household basic and/or recovery needs

Intervention: Issue direct, unconditional cash transfers through banks

Access to Critical WASH Services

Aim: Improve access to water for humans and livestock

Intervention: Rehabilitate nonfunctional water points in water-stressed pastoral communities

But how exactly do you determine who is the most vulnerable when millions of people are facing chronic food and water insecurity in the midst of an unprecedented drought?

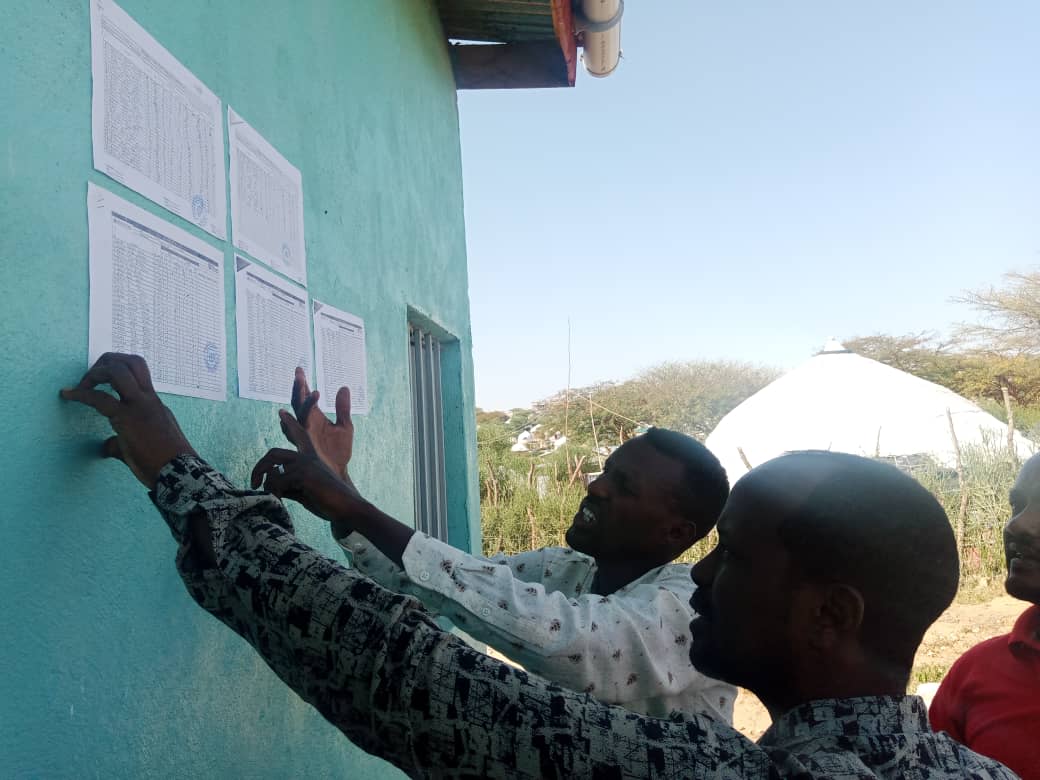

RIPA South turned to one of the three foundational pillars of pastoralism – community (e.g., social institutions, family) – for guidance. Between April and June 2022, Global Communities worked in close collaboration with RIPA South consortium partners (Goal and iDE), relevant local government offices and community members to identify, select and verify a total of 18,004 drought-affected households from 16 woredas and 80 kebeles to receive support under the project’s first Crisis Modifier.

According to Tadesse, because of resource limitations, that number represents just 1% of the households that need assistance in the areas where RIPA South is operating.

“Even though it might look insignificant in terms of addressing the caseload, it is impactful in terms of changing the individual household situations,” he said. “… We are creating some hope.”

Silbo Algo, DRM Committee Chair

Silbo Algo, DRM Committee Chair

Disaster Risk Management (DRM) committees that were established or revived at the kebele level with technical assistance and training from RIPA South were key to the selection process.

Rescuing and Restoring the Lifeblood of Pastoral Communities

On average, it takes at least five years for a pastoralist family to rebuild their herd following just one drought, much less back-to-back failed rainy seasons. Over the last year alone, Boru Kala, a pastoralist from Hamer woreda, has lost 20 of his cattle.

To help him and other pastoralists weather the devastating impact of this unprecedented disaster, RIPA South selected Boru and 4,465 other livestock-owning households to receive multi-nutrient livestock feed under the project’s first Crisis Modifier. The father of five said he was selected not only because of the cattle he lost but because the animals he has left are rapidly deteriorating. Like many other pastoralists, he has not been able to feed or seek medical care for his livestock to keep them healthy.

“I have observed that their body condition has reduced and the quantity of milk I have gotten from the cattle is not as much as before,” said Boru, as he gestured to an emaciated cow with clearly visible ribs. “This support means very much to me, because my livestock are suffering.”

In August 2022, Boru received 4.5 quintals (450 kilograms) of livestock feed specifically designed to quickly improve the body condition of drought-affected animals and boost their milk production. As part of the intervention, RIPA South trained Boru and other recipients on how to properly store and ration the feed for it to last up to three months for five cows per household.

Providing supplemental feed not only helps prevent livestock deaths and sustain livestock productivity but reduces the pressure on grazing lands and spurs regeneration that can help communities cope better in the future.

Cultivating Youth Skills to Sustain Livestock & Livelihoods

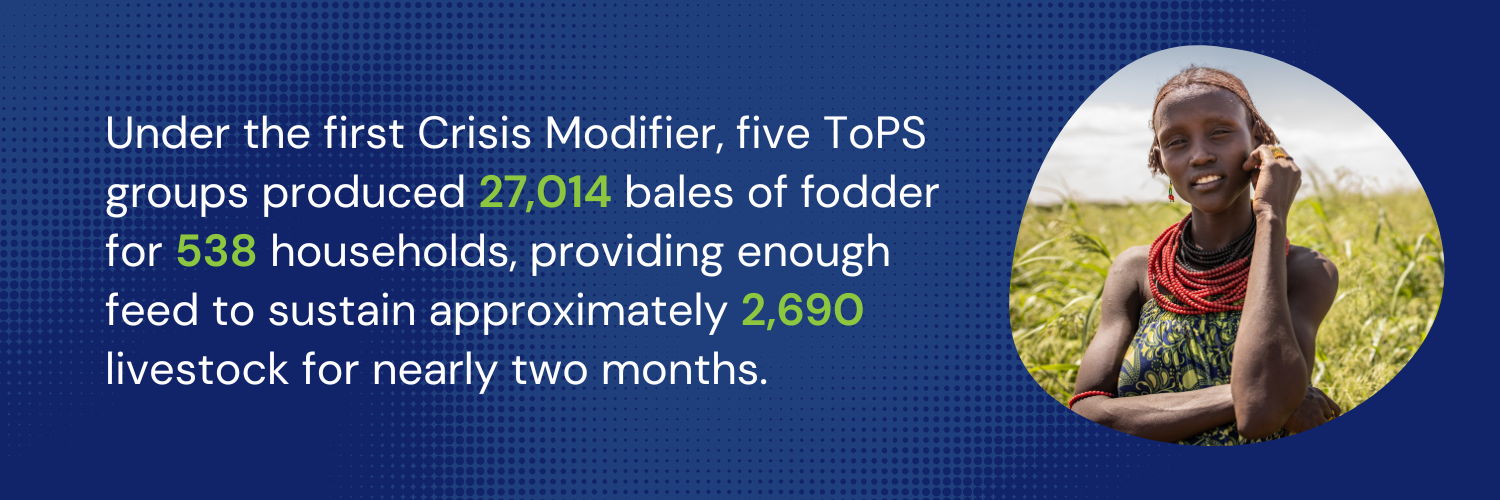

In addition to finding a local supplier of specialized livestock feed, RIPA South also worked with young adults seeking job opportunities beyond traditional pastoralism to produce fodder for crisis modifier recipients and commercial purposes. In late 2022, the project used two ToPs (Transitioning Out of Pastoralism) groups that had already been established and formed three more in the Dassenech woreda.

Each ToPs group includes 10-35 members, with balanced representation from both young men and women, to help close the gender gap in a sector typically dominated by men.

Abebe Lotuliya, ToPs Group Chair

Abebe Lotuliya, ToPs Group Chair

“Previously, we had a serious problem due to a shortage of feed. Our cattle were not feeding or grazing the land because of the drought,” said Abebe Lotuliya, chair of a ToPs group in Dassenech woreda. “Fodder development is very useful for us to protect our cattle and to feed our dairy cows.”

With support from RIPA South partners, ToPs groups received training on commercial fodder production from Jinka Agricultural Research Center and designated land on which to grow panicum grass, a drought-tolerant type of fodder that is good for erosion control and palatable to livestock.

Nabogna Tagna, ToPs Group Vice Chair

Nabogna Tagna, ToPs Group Vice Chair

“The dairy cows feed on this and release a lot of milk for our children,” said Nabogna Tagna, vice chair of a ToPs group in Dassenech woreda. “This is an improved type of forage.”

iDE facilitators also assisted each ToPs group with registering as a formal enterprise and obtaining a business license. As a result, they can generate income from both the sale of seed and fodder and deposit it into group bank accounts.

“Before, we did not have the skills to do this,” Abebe said. “Now, as a group, we have bought goats, food for household consumption and have saved a lot of money at the bank. We can protect our households.”

Apart from job creation and increased food security for ToPs members, the groups’ fodder production also helped to support a total of 538 drought-affected households in South Omo under RIPA South’s first Crisis Modifier, demonstrating how the project has been able to strategically blend humanitarian assistance with sustainable development activities.

Rehabilitating Water Points to Meet Critical Needs

Prior to the most recent rainy season (March-May 2023), 10.1 million people in Ethiopia could not access enough water for drinking, cooking and cleaning or basic sanitation and hygiene. Water availability has decreased significantly from all sources – boreholes, wells, collection ponds, etc. – due to ongoing drought. Damaged water points and dire conditions have forced many households into obtaining and consuming water from unhygienic sources, which has also led to serious health issues such as cholera outbreaks.

RIPA South’s WASH access intervention plays a critical role in ensuring year-round water supplies for both humans and livestock, particularly in water-stressed pastoral communities where water shortage has been exacerbated by the ongoing drought. Together with local water offices and woreda officials, the project began by obtaining a list of non-functional water points from each woreda where it operates and assessing which ones required minor or major rehabilitation.

Of the 274 water sources assessed, 100 needed repairs ranging from new handpumps and other service parts to total reconstruction.

The Ellekolom water point, which serves more than 100 pastoralist families from the Terongola kebele of Dassenech woreda, is one of 100 water points that was made operational again over the last year. Prior to its rehabilitation, community members had to walk over 6 miles to retrieve water from a local river, a journey that was all the more arduous for people and livestock already suffering from malnutrition and dehydration.

“Before [the drought], it was green enough and there was rain regularly. The land was covered by grass, and the cattle and livestock were excellent. That was before,” said Makolo Lowoy, a pastoralist who serves as vice chair of the WASH committee that manages the Ellekolom water point. “In the last five years, our livestock has died in many numbers. If you go down this bush and just walk a ways, you can see the bones. We almost lost all of them.”

Sitting under a small sliver of shade on cracked, desolate land that stretches for miles, Makolo and other members of the WASH committee shared how the rehabilitated water point is just 4 km (less than 2.5 miles) from their village and a godsend for their community during such a difficult time.

WASH committee, Ellekolom water point

WASH committee

“Now we’re getting water from here and cooking. It’s very beneficial for the family and the children,” said Egura Gure, treasurer of the WASH committee. “... When I am far away buying food at the market, I will not worry anymore, because the water is nearby. Even the goats will come after they are on the bush, and they will come and get water.”

RIPA South assisted the community with setting up a WASH committee to handle long-term maintenance of the water point, introducing them to relevant government officials at the woreda level and training them on how to adopt a fee-based system for water use. Households are typically charged 10 Ethiopian Birr per month to collect water, and that money is placed in a savings box to fund any necessary repairs. However, Makolo said current economic hardships have forced them to forgo collecting any fees right now.

“We are not contributing until we have recovered a little bit,” he said. “The women are getting some firewood, and they go to town to try to sell it. When they get that money, it is for the household to survive.”

Eventually, the community would like to set up a microfinance account and use their savings to convert the water point into a solar-powered system, but they acknowledge having a consistent source of clean water is still more than others have. In places where households must rely on ponds, rivers and other unprotected sources prone to contamination, RIPA South has distributed sachets of water treatment chemicals for families to use as needed.

Providing Vital, Dignified and Immediate Support through Flexible Cash Assistance

On a hot afternoon in August, Yerkol Lokoyo stood outside the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia in the Dassenech woreda of South Omo, with a broad smile on his face and 5,000 Ethiopian Birr (approximately $100) in hand. It was the first time the widow and father of 11 had ever withdrawn money from a bank account, and the first opportunity in months he had money of his own to buy essential items for his family.

Yerkol Lokoyo, multi-purpose cash assistance recipient

Yerkol Lokoyo, multi-purpose cash assistance recipient

“I have two children who still live with me who are waiting at home, so I am going to the market to buy clothes for them and food,” he said. “Previously, I had livestock. Now, since the drought happened, all my livestock are dead. … I haven’t any kind of cattle.”

Yerkol and his family were one of 4,000 households selected to receive multi-purpose cash assistance under RIPA South’s first Crisis Modifier last year. Over the course of three months, the project transferred 15,000 Ethiopian Birr (approximately $300) to each recipient, with priority given to the most vulnerable, including women-headed households, older adults and people living with disabilities.

Aras Elemu, multi-purpose cash assistance recipient

Aras Elemu, multi-purpose cash assistance recipient

“I am going to purchase food for my children and then I am going to purchase a goat,” said Aras Elemu, a widow with 9 children, 3 of whom still live at home with her. “I haven’t a husband, so this feels like God has given this for me. Another time when I am hungry, I will come to withdraw what I’ve kept in the bank to restock the food.”

Under the first Crisis Modifier, RIPA South distributed 60,000,000 Ethiopian Birr ($1.2 million) across 4,000 households, benefiting a total of 30,847 people (of whom more than 47% are women).

Before sending the cash transfers, RIPA South helped designated recipients obtain identification cards, open bank accounts and plan how to make the best use of the cash support during this challenging time. While basic commodity prices have increased, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) reports household purchasing power is 40% lower than average. Multi-purpose cash assistance is intended to help those in need buy food baskets, farming inputs, basic household items and health care without resorting to negative coping mechanisms.

For Oyita Kala, a pastoralist from the Hamer woreda, the support has been priceless – a fundamental key to restoring his identity, providing for his family and reconnecting with his culture after a devastating string of losses.

“For a pastoralist without livestock, life is very different. I was struggling very much. Not only me, but my children,” he said, explaining how cultural ceremonies and everyday activities center on having goats, cows and other livestock to trade, breed, sell, milk and use for household consumption. “If you don’t have the resources, it is difficult to participate.”

After receiving the first two cash transfers from RIPA South last August, Oyita bought four goats and food for his family and then set aside the remaining cash in his bank account – noting the security of both those decisions.

“The reason why I selected goats is they are drought resistant, and pasture is more available for goats than cattle,” he said. “... The benefit of putting the money in the bank is that I don’t have fear of losing that money. I know it is in a safe place.”

Over time, Oyita said he hopes to build up to owning cattle again by fattening his goats, selling them for a profit, buying more goats and repeating that cycle until his income is stable enough to exchange them at the market. Until then, like so many others in his kebele and across southern Ethiopia, he must focus on the moment at hand.

“For now, I am happy and hoping that the number of these goats will increase so that the lifestyle of my family becomes better,” he said. “Today, I am confident that my pastoralism will continue.”

While completing target activities under the first Crisis Modifier, RIPA South activated a second Crisis Modifier in December 2022 to continue to address the high caseload and surplus of needs arising from the complex humanitarian situation in South and southeastern Ethiopia.

Under this most recent influx of emergency assistance, the project is on track to benefit 97,410 people and 204,955 livestock with access to animal feed, veterinary care, multi-purpose cash assistance and improved WASH services in 2023.

Disclaimer

This project is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this story are the sole responsibility of Global Communities and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID or the United States Government.

Credits

Photography:

Genaye Eshetu, Jessica Ayala and RIPA South Staff

Video:

Jessica Ayala and Kallista Zormelo

At a time when disasters and disruptions are becoming more common and catastrophic, Global Communities, together with our local partners, equips communities with the training, tools and resources they need to recover from crises and build long-term resilience in the face of constant change.

From prevention and adaptation to positive transformation, we focus on solutions that center local voices and expand opportunities for growth, leadership and advancement.